The Circles - Book Four - Chapter 16

The Circles - Book Four - Paths Both East and West

Chapter Sixteen

On Becoming a Man

Written by Angmar

Tarlanc brought the wineskin back to his lips, drank deeply and then wiped his mouth off with his sleeve. "Lasses, I trust that I have not put you to sleep with my long tale." Turning his head first to the right and then to the left, he looked questioningly into the face of each girl.

"Oh, no, not at all," Elffled quickly assured him.

"No, Tarlanc, I insist that you continue," Elfhild implored. "I am not at all sleepy, but you have put in a very long day. Perhaps you might need rest?" She swatted away a small gnat which had been attracted to the odor of Tarlanc's wine.

"Nay, lass, not at all." Corking the wineskin, he placed it down on the blanket by his leg. "Some say that as you get older, you require less sleep. Since I am nearly a hundred, perhaps I do not need to sleep at all," he chuckled wryly. Of course, saying that it was unnecessary for him to sleep was an exaggeration, but Tarlanc always derived a good bit of satisfaction at the surprised look on others' faces when he casually told them his great age.

"One hundred!" Elfhild's mouth dropped open. "You look much younger!"

"A mere twig still green on the branch," he laughed, his eyes crinkling up with amusement at the slightly naughty meaning of his words. "Not entirely chaste and pristine in intent," he thought, "but not exactly prurient, either. Surely not even these two sheltered maids would be offended at such a mild impropriety." Since neither seemed to have noticed or paid any particular attention to his remark, he assumed that they were either both more innocent than he had first thought, or were ignoring his remark out of politeness.

"You must remember, lasses, that the Gondorians live a long span of time and therefore age less quickly. Most of my foresires attained venerable old ages." As Tarlanc spoke, Haun stood up. After yawning and stretching, the dog stuck his muzzle between Tarlanc's outstretched hands for a pat. "Had not heard this story, had you, sir?" Tarlanc asked him as he scratched between the dog's ears.

Elffled reached out hesitantly to pat Haun, and after Tarlanc had steadied him with a soft word, Elffled was overjoyed when the mastiff allowed her to lay her hand gently upon his head. "Do you think he likes me, Tarlanc?" she asked hopefully.

"Aye, lass," he nodded. "Haun is a good judge of character. Now you two become friends while I resume telling my story!"

"Yes, please!" Elffled smiled as she stroked the unresisting mastiff's head.

"Well, lasses, after the tribe had camped at the outskirts of Minas Tirith for two weeks, they set off for the south near the end of October. Our journey was made in admirable time, and within a fortnight, we had reached our destination - Pelargir. The broad plains near the city had been the Randirrim's winter camping ground for years, favored by the tribe for its mild climate and warm winters. The large inland port attracted commerce from many different lands, and it was fascinating to a country boy like me to sit on the dock and watch ships sail by with their colorful flags unfurled in the breeze. Pelargir was a thriving, prosperous city, home to many merchants who dealt in both import and export; warehouse owners; craftsmen; ship builders; and all the myriad of trades, crafts and occupations which attend the operation of any large port city.

"The men of the tribe employed themselves with making jewelry, furniture and other crafts, while the women were in charge of selling the goods. These they marketed from the open backs of their wains, displayed in small tents or stalls, and even in some cases, sold from door to door in the city. While the Randirrim were not completely accepted by the people of the city, they were tolerated as long as they stayed out of trouble. Or as Mere and Peri were fond of saying, 'As long as you do not get caught.' The twins certainly followed their own advice, for never as long as I was with them were they ever apprehended, though they did get into some tight situations.

"During the winter, Warasija, the brother of Ahãma, died, leaving his widow, Hebeli, and their grown son, Dezi, bereft. Dezi was a simpleton, incapable of learning any skills more complicated than what a small child could master, and so his father's trade of jewelry-making died with him. The young man was a huge, gawky fellow with a wide, broad face; dull, black lackluster eyes; fleshy red lips; a large, bulbous nose; a neck thick as a bull's; wide, powerful shoulders; massive, brawny arms; a gut as tight and well-muscled as the rest of him; and legs as big around as small trees resting upon a solid foundation of wide, strong feet. In all of my life, I have never seen a man stronger than he was.

"Hebeli and Dezi would have fallen on grievous times had not Ahãma and Wedri invited the widow to combine her resources with their own. It was decided that when spring came, Hebeli would drive her own wagon, while Meri would assist her son in caring for their stock and helping around the camp. I was just as glad that it would be Meri who would be helping his aunt and cousin, rather than me. While there had never been any trouble between Dezi and me, I had never felt at ease around him. Occasionally he would have a tantrum after his mother had withheld some food or object from him. Though he would never become violent or threatening, he would go away by himself, babbling and muttering as great quantities of spittle and phlegm ran from his mouth, dribbling over his chin and running down his neck. There he would stand for hours in the woods or some quiet place, rocking and swaying from side to side, and never seeming to become fatigued.

"Though he could learn little else except simple things such as sorting beads and jewelry fasteners into containers, there was one thing at which Dezi was an expert, and that was wrestling. He loved the sport so much that he had submitted to the rules held in common by the other wrestlers over all of Gondor. He had been forced to concede to this requirement after his refusal to abide by the rules had resulted in his injuring a man so severely that the fellow had almost died. After that, Dezi had not only been able to master the rules, but he was able to quote them word for word. Often he would be found by himself, reciting the rules to a bird or squirrel perched in a tree, or demonstrating the various moves and holds with pieces of rope and sticks.

"Other than Warasija's death, the winter passed without incident, and the spring had returned almost before I was aware of it. Once again we were on the road north, but Wedri had decided that we would not pass through my village that year, for it was far too risky for me. We spent the rest of the summer traveling in Anórien, where we usually received permission to camp on the outskirts of hamlets. These times of commerce between the villagers and the Randirrim provided the main opportunities for the tribe to earn a livelihood, for seldom did anyone trust them enough to hire them for seasonal labor, though they did welcome the chance to purchase goods from them.

"Besides selling baskets, furniture, jewelry, leather goods and other merchandise at these gatherings, the men and women of the tribe offered certain other services to the townspeople. Perhaps when I tell you of what these things were, they will come as a shock to you. Some of the women and a few of the men were gifted in divining the future by looking at the lines upon the palms of hands, or inspecting the spent leaves of tea, or employing balls of crystal or cards with strange drawings and designs upon them, and other methods even more bizarre than these. Perhaps it is better that I should not detail these latter ones to you.

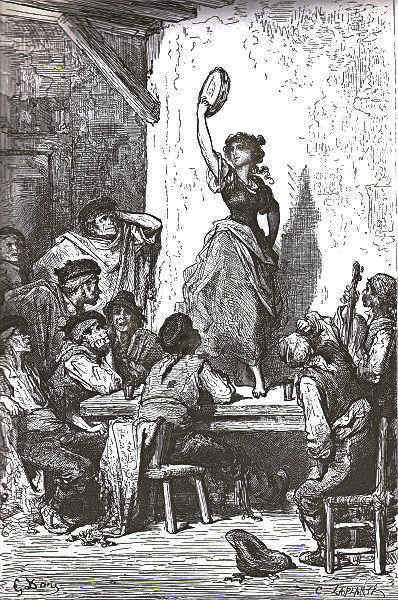

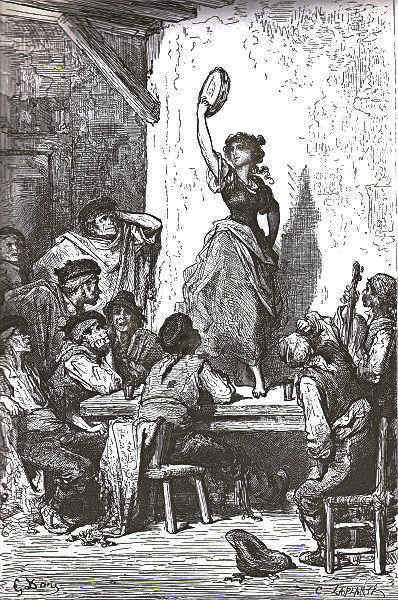

"While their mothers and aunts earned money by looking into the future, many of the maidens would dance for coins thrown to them by the village men, who were eager to see them dance. These dances would be strange and foreign to you, and I have been told that they originated long ago in the East from whence the Randirrim originally hailed. Wearing bright, gaudy clothing and gleaming metal jewelry, the women twirled and shook their bodies, moving in ways that the staid Gondorians thought were scandalous. The young bachelors evidently were not bothered by the poor reputation of the Randirric dances, for they were frequent visitors at these exhibitions. I had heard that sometimes the married men would sneak away to watch the dances, but I would wager that if their wives ever found out, these indignant matrons would banish their husbands from their beds if they did not resort to physical violence first," Tarlanc chuckled.

"While their mothers and aunts earned money by looking into the future, many of the maidens would dance for coins thrown to them by the village men, who were eager to see them dance. These dances would be strange and foreign to you, and I have been told that they originated long ago in the East from whence the Randirrim originally hailed. Wearing bright, gaudy clothing and gleaming metal jewelry, the women twirled and shook their bodies, moving in ways that the staid Gondorians thought were scandalous. The young bachelors evidently were not bothered by the poor reputation of the Randirric dances, for they were frequent visitors at these exhibitions. I had heard that sometimes the married men would sneak away to watch the dances, but I would wager that if their wives ever found out, these indignant matrons would banish their husbands from their beds if they did not resort to physical violence first," Tarlanc chuckled.

"Did you ever attend any?" Elffled asked mischievously.

"You did not think I would miss them, did you?" He cocked his head to one side and wrinkled his nose at her.

"Somehow I did not think so," Elffled giggled.

"Before I finally left the Randirrim, I had even learned a few of the dances myself." Seeing the surprised expressions on the twins' faces, he added, "Even had my future read several times. I wanted to know what would happen to me, whether it would be good or ill."

"What did the fortune teller say?" Elfhild asked, curious.

"Hebeli, Warasija's widow, was the first to read my palm, but later Ahãma verified what she had said, by mixing sand with wine and stirring it with a stick and telling me what the swirling patterns meant. I never really questioned their words, and many of the things they told me have come to pass."

"What were they, Tarlanc?" Slightly alarmed, Elffled put her hand on his arm.

"They said that when it came to important matters, I would always take the path which I had never chosen, but take it I surely would, whether I wanted it or not. That is the way it has been all these years with little variance. My life has been far too long to tell you all that happened to me, however."

"Tell us something, please," Elfhild pleaded.

"Something, but not much more. It is growing late, and the candle is burning lower. I had lived with these people for three years and grew to manhood among them, finally being adopted by them when I was eighteen. There were no happier years of my life than these, and if things had not happened as they did, I would probably still be among them." Tarlanc's brows furrowed solemnly and his eyes grew sad with a faraway look in them.

"Tarlanc, dear Tarlanc! I sense something sorrowful from your past! If it bothers you, I entreat you not to tell us." As she looked at him intently, Elffled fretted and worried her bottom lip.

"Lass, while the hurt is still there, many years have passed, and now it is just a small hurt. You remember I told you a little about Tabahaza, whom I said was a shy young girl. Over the years, we found ourselves more and more in each other's company, and I began to grow to love her. We would find ways to be together, sometimes riding beside each other when we traveled; other times leaving the camp and walking alone through the woods and fields.

"Then one night when we were sitting on the banks of a small stream with the moonlight streaming down upon us - surely a night meant for loving - I became bold, took her in my arms and kissed her for the first time. We were both left breathless with the passion of that first kiss, and I knew that this was the only girl whom I would ever love. With her warm, young body in my arms, I completely lost my reason and kept pressing her for more and more. Before the night was over, both of us had tasted passion's wine to its sweet depths. When I at last I came to my senses and realized how I had compromised her, I asked her to be my wife, and she consented. I vowed to her that the very next day I would ask her father to let me take her as my wife in whatever ceremony tribal traditions prescribed.

"The next morning, when I went to ask Wedri for her hand, a cloud of despair was hanging over my heart, for I knew that he would refuse to allow me ever to wed Tabahaza. I was a foreigner, not of the Randirrim. Therefore, it came as little surprise to me - though the pain was no less devastating - when he refused. His rejection was harsh and scornful, and he laughed in my face. As I left the wain, he added, still laughing, 'No foreign stripling will ever be my son-in-law! Never be fool enough to ask me again, boy!'

"I had not gone many steps when Ahãma caught up with me, slipping into stride beside me. 'Do not pay attention to Wedri! He is a big fool, never means what he says!' She was a high-strung woman, given to strong emotions, always motioning and gesticulating with her hands as she spoke. My face turned crimson in embarrassment, for I was sure the whole village would hear her. She suddenly stepped in front of me, grabbed me by the shoulders and stared up into my face. 'You silly boy! Of course Wedri wants a strong, white-skinned boy like you for son-in-law. You make beautiful children with Tabahaza! They will all grow to be strong, big handsome people, and he will be proud of them! Insist that the marriage was his idea in the first place! Just wait a few days before asking him again.'

"'But he said never--' I started to interrupt her.

"'Hush, boy!' she scolded me. 'Do not talk when your mother-in-law is speaking!'

"Many of their neighbors were milling around us, laughing and smiling and adding their own comments on the advantages and disadvantages of the union. When I tried to excuse myself, Ahãma pulled my face down to hers and kissed me once on each cheek. Giving a hasty excuse that I had something to do, I pulled out of her embrace and sped away to the sound of the uproarious laughter of Ahãma and her friends. Some time later I learned that after I had gone, Ahãma went to Wedri and impressed upon him the good sense of having another strong back in the family. Faced with this irrefutable logic, he put aside all of his opposition, and agreed with his wife. The wedding was set to be held that autumn when we arrived at Pelargir for the winter.

"A few days after the betrothal was announced to the tribe, I was taking the horses to the stream for watering when I thought I heard heavy steps behind me. As I turned around, I grimaced when I saw Dezi lumbering along behind me, his long arms swinging, his huge thick legs striding purposely along. Wishing no trouble with him, I waved at him and then continued leading the horses to the stream. Just as the animals dipped their muzzles into the cool water, I felt the presence of someone right behind me. From the sound of the person's raspy breathing, I knew it must be Dezi. A heavy hand slammed down on my shoulder, and as I was spun around, the reins slipped from my fingers.

"I was determined not to show him my fear, and to bluster my way through any mischief he might have planned. 'Ho, Dezi. Came to watch me water the horses, did you?'

"A bristling maelstrom of fury, Dezi stood there in front of me. 'No,' he growled, 'come to warn you.' With those terse words, his hands shot forward, his meaty fingers grabbing the shoulders of my shirt. I gasped as he swung me up into the air to face him.

"'Warn me of what, Dezi? Stop playing now. You might tear my shirt, and I have only two!' As I looked into his dull-witted eyes and breathed the rank stench of his breath, I had the impression that the game he was playing could be lethal.

"'Who cares about your shirt? You will not marry Tabahaza! You are not worthy of her! Maybe I will break the bones of your face so you will be ugly, and she will not like you anymore!' As though I weighed no more than a child's rag doll, Dezi held me in the air, the soles of my boots an inch or so above the ground.

"'Is that what you want to do to me, Dezi? I do not think I will like that very much,' I taunted him. Though Dezi was incredibly strong, he was not particularly fast, and his dulled eye did not catch the quick movement of my hands as they darted towards his face. He bellowed in rage as I jabbed my thumbs into his eyes as far as they would go. Screaming in his pain, he flung his hands to his eyes, releasing his hold on my shoulders. I was ready for him, landing easily on my feet. No sooner had they touched the ground than I brought up my knee and slammed him hard in the groin.

"'You have ruined me, you bastard!' he shrieked as he almost bent double in pain.

"'I do not think so,' I sneered as I landed a kick at Dezi's tortured loins. 'Maybe now you are!' I laughed as he doubled up and sank to the ground like a felled tree. As he lay there writhing, I quickly took the cord that served as my belt and tied his wrists and ankles together, pulling his hands and feet up until he resembled a crescent moon. Then I went to find the horses, which had trotted away to safety during the fight. Feeling quite proud of myself, I mounted one of the animals, leading the others behind me, and headed off at a gallop for the camp."

"While their mothers and aunts earned money by looking into the future, many of the maidens would dance for coins thrown to them by the village men, who were eager to see them dance. These dances would be strange and foreign to you, and I have been told that they originated long ago in the East from whence the Randirrim originally hailed. Wearing bright, gaudy clothing and gleaming metal jewelry, the women twirled and shook their bodies, moving in ways that the staid Gondorians thought were scandalous. The young bachelors evidently were not bothered by the poor reputation of the Randirric dances, for they were frequent visitors at these exhibitions. I had heard that sometimes the married men would sneak away to watch the dances, but I would wager that if their wives ever found out, these indignant matrons would banish their husbands from their beds if they did not resort to physical violence first," Tarlanc chuckled.

"While their mothers and aunts earned money by looking into the future, many of the maidens would dance for coins thrown to them by the village men, who were eager to see them dance. These dances would be strange and foreign to you, and I have been told that they originated long ago in the East from whence the Randirrim originally hailed. Wearing bright, gaudy clothing and gleaming metal jewelry, the women twirled and shook their bodies, moving in ways that the staid Gondorians thought were scandalous. The young bachelors evidently were not bothered by the poor reputation of the Randirric dances, for they were frequent visitors at these exhibitions. I had heard that sometimes the married men would sneak away to watch the dances, but I would wager that if their wives ever found out, these indignant matrons would banish their husbands from their beds if they did not resort to physical violence first," Tarlanc chuckled.