The Limekiln by Elfhild

When the storm's fury had at last abated, Fródwine set off on his long legs with his brothers scurrying to keep up with him. They walked under the dripping branches until they came to a glade, grown up with small bushes and bordered by the great trees of the wood. Here, Fródwine ordered them to strip and drape their wet garments over the bushes to dry in the sun, which had burst out in radiant, bright splendor, as though to compensate for the darkness of the tempest just past.

One huge and mighty oak had been uprooted by the winds. Crashing down, the giant had taken lesser trees with it in its death throes, smashing them to the ground and crushing them beneath its thick trunk and copious branches. Unwilling to sit upon the damp ground, Frumgár and Fritha climbed up on the felled trunk and watched as Fródwine walked to a mangled young ash. The sapling's base had been almost splintered in twain by the force of the mighty oak's fall.

"Frumgár!" came his elder brother's sharp command. "Get off your lazy bottom and help me with this tree!"

"What are you going to do with it? came Frumgár's grumpy-sounding voice as he hopped off the oak trunk.

"You will see."

Together, the two boys pushed and shoved at the young ash until they had broken it off near its bottom. Propping the base end of the tree against the oak trunk, Fródwine set to work, hacking and sawing at the wood with the orc knife until he had cut off the bushy head of the tree.

"Watch me and learn," he commanded in a condescending tone of voice as he held the smaller end of the sapling in one hand and began trimming the wood to a sharp point with the orc dagger. "Those skills which I learned in Father's carpenter shop will stand me in good stead with this business. Perhaps when we return home, I will start my own shop and make both weapons and farm implements." As he skillfully trimmed off pieces of bark and wood, the shavings grew into a small pile at his feet.

"Fródwine, you must think that I am a complete lackwit!" Frumgár muttered in offended dignity. "Perhaps you have forgotten that I have witnessed all your efforts to create weapons. Yesterday's attempts at making a spear from a dead branch turned out none too successful, and you finally discarded it as being of little value."

"The ash is straight, the wood is strong, the point is sharp, the range is long," Fródwine hummed to himself as he whittled on the sapling.

"And your poetry is as bad as ever, and I may add misleading. The spear is far too short, heavy and crooked to have any range at all." Frumgár smirked in pleased satisfaction as he walked back to resume his seat on the fallen oak.

Testing the balance of the spear in his hand, Fródwine made a few preliminary thrusts with the weapon before ambling over to where Frumgár and Fritha sat on the butt of the oak. Smirking triumphantly, he brought the spear forward, touching the sharpened tip against Frumgár's bare stomach. "What do you say to this?" he smiled pleasantly as he pushed the sharpened end deeper into his brother's stomach.

"I would say you have been successful today, brother, and you have proved your point rather well," Frumgár whispered as he looked uncertainly down at the spear and then into his brother's eyes. Sometimes he wondered if his brother would enjoy killing him.

"Aye, I believe I have been," Fródwine grinned as he dug the spear point deeper into his brother's stomach. Laughing, he took a step back, placed the hilt of the spear on the ground and leaned against the shaft. "Now with the orc dagger and this spear, I believe that we stand a far better chance of protecting ourselves. We will rest here a while longer until our clothing has finished drying, and after having a bite of nourishment, we will resume our journey."

After the tempestuous storm of the afternoon, Midsummer Eve brought fair weather, a cloudless, star-ridden sky and a waxing moon which shone silvery bright like a shield of mithril. The rain had plummeted down in torrents, but the thirsty earth had consumed the waters totally, licked its parched lips and begged for more.

"Can I carry the spear, Fródwine?" Fritha asked hopefully, eying the weapon as eagerly as if it was a prized new toy.

"Do you think you can wield it?" came Fródwine's brusque reply.

"No, I guess not," Fritha replied, disappointed, his feelings hurt. He and Frumgár fell into step behind Fródwine, and the usually talkative youngest boy lapsed into silence.

"Brothers, we are fortunate," Fródwine broke the silence. "The ground drank up most of the water, and so our feet should not get too wet." He guided them along the banks of the small stream which he had followed earlier in the day. The brook, strengthened by the waters which had rushed forth from the skies earlier, had spilled over its banks during the height of the storm. Though its level had since dropped considerably, still the water growled angrily as it rushed tumultuously on its way to the Anduin.

Leaving the stream, Fródwine set a westward course through the woods. Deciding to venture out into the expanse of clear land between the eaves of the forest and the mountains to the south, he took a risk and stepped out into the open. Seeing no evidence of enemies and deciding it was safe, Fródwine led his brothers out of the trees, and walking on, they came to an old road, long abandoned.

"Lads, though this road is now deserted, if you will but inspect the land around it carefully, you will see that this road has had use sometime in the not too distant past. See how the dead grasses of last autumn still cling to the soil on both sides of the road, but in the midst of the roadbed, the ground has been churned up, as though by many hooves?"

"Aye, brother, I see what you have pointed out. Undoubtedly forces of the enemy have used this road not too long ago." Frumgár bent down and inspected the roadway.

"Though it is tempting to walk along this pathway, I do not want to take the chance that we might meet an enemy patrol." Fródwine's brow furrowed in concern. "Therefore, we shall take to the woods, striking a course parallel to the road."

"Oh, Fródwine! Not more woods!" Fritha whined, looking down at his scratched ankles. "I keep tripping over the brambles!"

"Hush, baby!" Fródwine growled. "Just lift your fat little legs higher, and you will not fall so much!"

"They will not go any higher!" Fritha complained, biting his lower lip in frustration.

"Be quiet! Not another word!" Fródwine warned. Sometimes he felt like boxing his little brother's ears. Such a baby! At least Fritha stopped his whining.

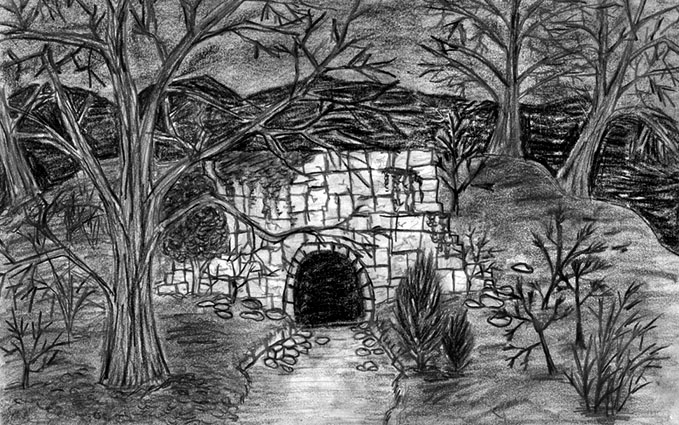

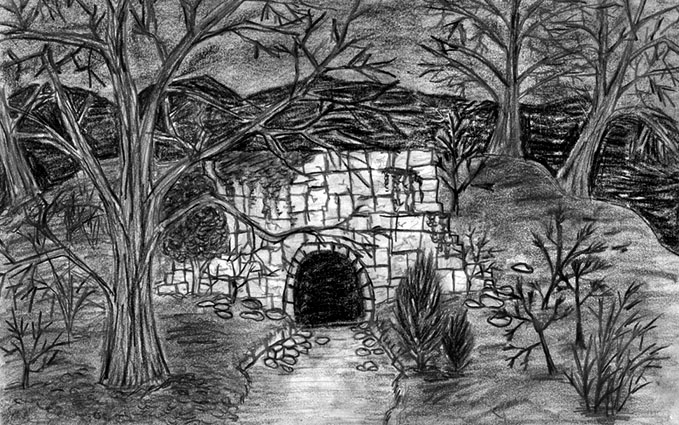

Crossing over the road, the boys journeyed onward, keeping the foothills of the mountains to their left. Following along the contours of the land, they rounded a rock outcropping that thrust out into their path. Passing by the steep bank, they came to a clearing. Before them, looming out of the darkness like a great wall, was the flat face of a large stone structure.

Set into the slope of a small knoll, the ruins of an old lime kiln brooded sullenly. The sight came into their view unexpectedly and took the boys completely by surprise. Appearing much like the barbican of a deserted castle, the structure jutted out like a stark barrier, though there was no castle to be seen, only the hill into which three of its four sides had been built. The rounded arch of the kiln's entryway was dark and foreboding, like a portal leading into a mysterious chamber of abysmal darkness. Resembling a castle in appearance, perhaps -- or a barrow ancient and weathered by time, its somber door leading to the resting place of the dead. Yet though its gloominess was heavy and oppressive, the shadowy tunnel appealed to an innate sense of lurid curiosity and beckoned as much as it repelled.

Now abandoned and forgotten, at one time the deserted structure had been the site of a prosperous lime burning industry. Limestone had been taken from the Stonewain Valley and then borne on carts drawn by horses to the kilns. Then from the wells at the top, the men would dump limestone down into the fires. Fires were kept burning almost continuously in the bowl-shaped chamber at the base of the kiln, a work so hot and exhausting that a quart of beer was considered a fair part of the lime burner's wages. As each layer of limestone was added, more wood was thrown in until the limestone and burning timber reached near the roof of the kiln.

The powdered lime which was drawn off at the bottom was extremely hot and caustic, a dangerous substance with which to work. Enduring the thick smoke and noxious fumes and facing the possibility of asphyxiation, the workers loaded the lime into barrels which were to be hauled away to Minas Tirith and there used in the making of mortar, plaster, white-wash, cleansers, or spread over the fields to improve the tilth and vitality of the soil.

Years before, the industry had moved further south. No more did the flames belch from the open wells at the top to pierce the sky and set the night aglow. The laborers who had sweated and struggled in the burning of limestone had in time turned into dusty bones, themselves resembling now the powdery limestone which they had once burnt. The boys, of course, knew none of this, and true it was that the only record of the history of the lime burners existed now in dusty tomes stored and basically forgotten in archives in Minas Tirith. These accounts were seldom of interest to anyone, except an occasional scribe who chanced upon the story, and, upon reading it, thought it but a quaint tale from the past.

Silvery moonlight shown down, illuminating the pale blocks of the forsaken structure and the loose bricks which lay scattered around its base. Crawling up its weathered sides were the brown skeletons of withered vines and tufts of dead grass which set their roots into the places where the bricks had grown soft and crumbly with time. A few barren branched trees rose up around the kiln, the moonlight shining off the gnarled limbs, casting spidery patterns of light and dark which shifted as a soft breeze stirred the naked branches.

"What is that, Fródwine?" Fritha asked in a whisper, afraid to speak any louder. The youngest boy pushed closer to Frumgár's side and clung tightly to his hand as he always did when he was frightened or distressed.

Fródwine was silent for a few moments before replying. "From the little I can see of it in this darkness, anything I would say would be only conjecture. Perhaps it is the base of a tower or a fane, dating back to the Old Ones of ancient days, but who can say for sure?" He shrugged his shoulders, having little interest in the venerable structure.

Frumgár, with Fritha holding tightly to his hand, walked parallel to the base of the kiln and peered up to the uppermost level. "Look, Fródwine, there is a gentle slope along the side leading to the top. Could we not explore and attempt to determine what it might have been?"

"Becoming brave, are you, lad?" Fródwine chuckled in that mocking tone that had become so much a part of his nature here of late.

"No, just curious," Frumgár replied testily. "It does not take much bravery to walk up a slope."

"Go on," Fródwine replied indifferently as he settled his back against the trunk of a gnarled oak. "You should be safe enough. If there were orcs about, we would have seen some sign of them, or smelled them. You know what a stench they leave in their wake. I was about to call a halt to rest for a while anyway. Just keep your eyes alert in case there should be any adders or other such serpents about. Oft times, they dwell around piles of rock or abandoned buildings."

"I will keep my eyes open," Frumgár replied and glanced down to Fritha. "If you prefer waiting here with Fródwine, little brother, I will go atop and look about."

"No! I would rather go with you!" Fritha glanced warily at Fródwine and then turned pleading eyes upon Frumgár. "You were not going to go inside, were you?" Fritha asked in a lower tone, obviously having second thoughts. "It is dark and scary, you know."

"No, we are not going inside. We have no torches, and besides, I have no desire to meet serpents in the dark," came Frumgár's matter-of-fact reply. He led Fritha along the base of the kiln, searching for a way up the knoll that would keep them out of the underbrush and rubble. "Here, follow me!" he exclaimed as he sighted a route to the top. The incline that Frumgár chose was relatively gentle, and soon the two boys neared the top of the grade.

"I did not want to stay down there with Fródwine," Fritha confided in a voice scarcely above a whisper. "He is so cross and grouchy anymore that I would prefer not to be around him much."

"Fritha, do not be so harsh on your brother. He has much upon his mind. Now keep holding my hand... you remember what Fródwine said about snakes," Frumgár cautioned as they came to the top of the slope. There before them, the incline of the hill met the flat stone of the roof.

Fritha squeezed Frumgár's hand in acknowledgement that he understood. "There is not really much to see up here, Frumgár, only some old trees and shrubs," came Fritha's disappointed voice. "Say, I wonder what that is over there?" he queried, pointing to a shadowy indentation on the northern side of the roof. "Let us see!" He tugged Frumgár's resisting hand.

"Hold my hand! Do not go venturing off without me! You must be careful up here!" Frumgár warned.

"Nothing up here will hurt us. This is just the top of a hill!" Fritha gave his hand another impatient jerk. When his brother did not move as quickly as he wanted, he broke free and scampered across the stone roof.

"Fritha, come back here!" Frumgár called nervously. "Where are you?" His eyes searched over the roof of the kiln. When he could not locate the little boy, Frumgár's stomach tightened in a spasm of apprehension.

"I am right over here, Frumgár!" Fritha giggled. "Are you going blind?"

Finally catching sight of his little brother, Frumgár began closing the distance between Fritha and himself. "I did not see you," he replied brusquely, irritated with Fritha's games.

"It is a hole in the roof!"

"I can see that, Fritha! Now get back from it before you fall in!" A worried Frumgár became even more agitated at the sight of Fritha standing so close to the edge of what appeared to him to be the open pit of a well. In reality, this had been the top of the shaft leading to the furnace of the kiln. The aperture, which had once belched acrid smoke and fumes during times of lime burning, was wide and round like the circular opening to a deep well, and just as dangerous to the unsuspecting and careless.

"No, I want to look!" Fritha replied, determined to have his own way. He took a step closer to the great, gaping pit and bent down to pick up a small stone. "Do you think I am dull-witted? I am not a baby; I have sense enough not to fall in!"

"If you do not get back from there right now, I am going to call for Fródwine to come up here! If you do not do what I say, he will be very angry at you for disobeying!" Upset and becoming increasingly more alarmed, Frumgár quickly moved towards Fritha.

Fritha edged closer to the course of moss-encrusted limestone that lined the well from its top to its bottom. Tossing the stone down into the dark chasm, he listened until it thudded on the kiln floor some twenty feet below. "See? Nothing happened." Half turning to face Frumgár, Fritha giggled as he bent down to pick up another fist-sized piece of limestone.

Just as he waved to Frumgár, Fritha felt the limestone supporting wall beginning to give way, sagging under the weight of its great antiquity. As the rim sank, the sodden ground about it caved in, the sides of the wall slipping downward in a wet, oozing mass of dirt, deteriorated limestone and fire tiles. Screaming in panic, Fritha tried to jump back, but his feet slid out from under him on the muddy ground. Waving his arms wildly in the air, he frantically tried to regain his balance, but he was captured in the powerful force of the moving earth. Screaming again, he was sucked down over the edge of the precipice.

"Fritha!" Frumgár shrieked wildly.

More of the rock wall collapsed, the debris gaining momentum as it slid downward into the darkness, until it was like the crest of a mighty wave. As Frumgár stood helplessly at the top and screamed hysterically, Fritha was borne downward by the momentum of the sliding conglomerate of earth, fire tile and limestone. The wave swept him down until he was tumbled to the bottom of the old kiln. Throwing his hands in front of him to catch his fall, he screamed in agony as his left arm bore the brunt of his sudden descent. Lying on his back, whimpering in pain, he looked up to see a few loose stones break away from the rim. He tired to cover his face with his hands, but his left arm was clumsy. "Mother!" he whimpered as a stone struck his forehead. Then all went dark and he knew no more.