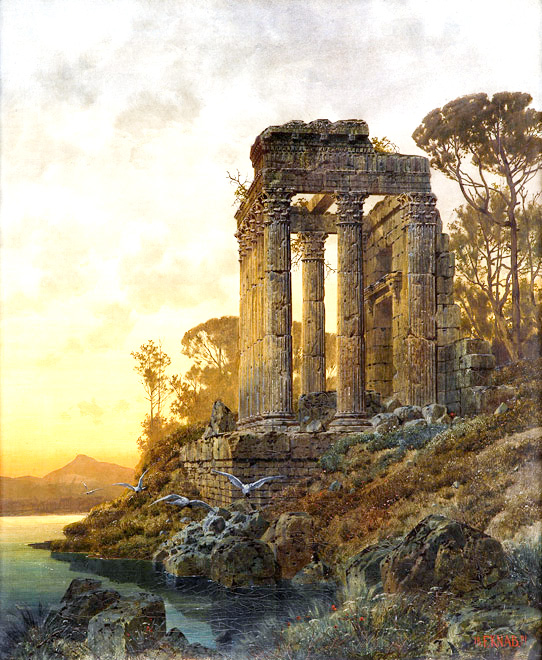

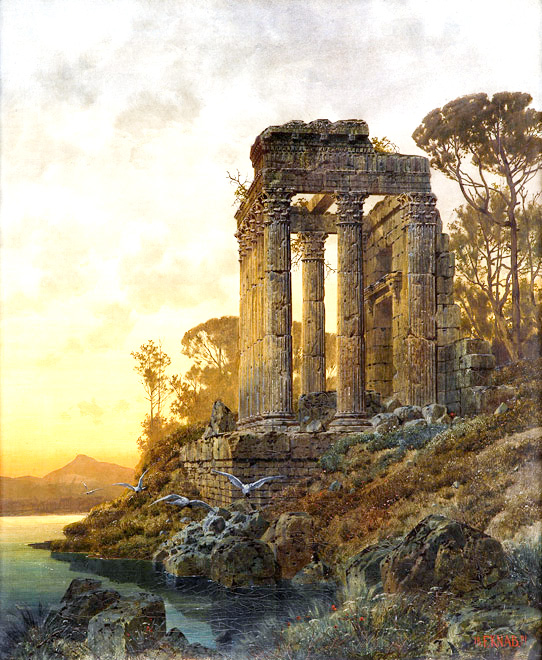

Art by Ferdinand Knab

Even though there was some time remaining before dawn, many of the women felt that sleep was impossible now that they had heard the revelations of Waerburh, Frithuswith and Aeffe. While some lay down by their slumbering children, others huddled about the campfire and continued talking until the light in the eastern sky denied them any further opportunity for rest.

Most of the captives were dubious of a successful escape, but the bolder ones vowed that they would at least venture an attempt. The timid ones, who quailed at the mere thought of challenging the strength and might of the slavers, pledged at least to assist their friends and kin. Secrecy was of the utmost importance, and so the women had decided the discussions would not commence until all of the children had fallen asleep for the night.

A horn rang out, its melodious strains summoning the captives to form into troops and line up for breakfast. Holding their bowls in their hands, the women and children looked into the faces of the kitchen slaves who doled out their morning portions of rice and lentils flavored with strange spicy essences. Those women who were firmly set in their hatred of their conquerors scowled at the young boys who toiled as scullions, for they saw them as enemies, even though they, too, were slaves. Many of the boys returned the women's frowns, though others smiled, flashing pearlescent white teeth.

After the breakfast was completed, the captives were marched back to the area where they had slept for the night. Formed into lines, the women were soon chained together. The demand – "Move forward!" –was shouted by the guards, and the procession was put in motion.

As the slave caravan began to move eastward, Esarhaddon and his physician Tushratta rode beside the captives. They held their horses' gaits to match the slow cadence of the marching feet, sometimes halting their mounts so that Esarhaddon could watch the parade of the wretched. His gaze languidly roamed over the women, following the contours of their curves as though he were caressing their bodies with his hands. Often he and his servant would talk in Haradric, the strange yet melodious tongue of the South, as he pointed with his riding crop to one matron or maid who had captured his fancy. This unwanted attention caused many a gentle face to turn crimson in embarrassment.

There was no denying that Esarhaddon made a striking, handsome figure on his horse, and many of women did not consider that his tawny features were quite so barbaric as they claimed they were to their friends. Even his strange garb of turban, flowing cloak, tunic and baggy trousers, and riding boots flavored a yearning for the unknown, the forbidden and the exotic.

Having been born into a horse culture, the women appreciated that the Southron was a capable horseman and rode his chestnut mare with an easy grace. The horse was a fine one of obvious good stock, though not as good, of course, as those of the Rohirrim. The mare was sleek, well-groomed, without blemish, and of a more delicate build than that of the Northern horses. Her face tapered down to a sensitive muzzle so refined that it could have easily fit into a cup – a Southern horse, native to the deserts and bred for speed and grace.

As the captives plodded towards their destination, they tried not to look at the slave-master, for his eyes were dark and fierce and quick to catch the impetuous glance of a maiden. His eyes had the look of a rogue, filled with mischievousness, even devilishness, with a touch of cruelty that seemed to lurk somewhere deep inside them. He was surely not a man who would take well to being disobeyed; that was obvious in the arrogant way he held his head and the cocky air which was natural to him.

In late afternoon, away in the distance to the east, the captives could see the ruins of huge structures, the remains of a great city where once the Gondorian kings had ruled – Osgiliath, steeped in its traditions, and home to no one among the ranks of the living. The waning sun looked deeply between the moss and lichen covered girders, but could do nothing to dispel the shadows that lurked under broken and tilting roofs.

As they drew closer, Esarhaddon halted his horse while three of his men joined them. Speaking in a boisterous voice, he pointed his riding crop ahead to a ruined structure which still held some degree of form in its aging deterioration.

"In that place reposes what remains of the King's House, and over there," he gestured, "is the Great Hall of Osgiliath. However, as you can see, no king rules here now. He has passed his scepter to the birds and beasts who are regents and reign here! Perhaps the ghosts of Isildur and Anárion, the sons of Elendil, mourn the loss of their city even unto this day!"

Casting furtive glances about their surroundings, the column passed them by and marched on. The Southrons scarcely looked at them, talking among themselves in that manner which curious travelers everywhere have when visiting a quaint landmark of the past.

After a short march through the city, the half-breed orc guards commanded the slaves to halt for the night. Waiting with the other women to be unchained from the line, Goldwyn thought she felt eyes upon her. As she glanced up, her eyes met those of Esarhaddon. Becoming angered at the bold expression on his face, Fródwine looked from his mother towards the slaver and then stepped protectively in front of her.

"Stay away from my mother!" he ordered with all the bravado of reckless youth.

Amused by the boy's defiance, Esarhaddon chuckled softly. "Lad, are you the warrior of the family?"

Coloring at the question, Fródwine kept his gaze bored on the slaver. "No, sir, I am a boy, not a warrior, but I will fight for my mother and my brothers."

"A little rooster whose spurs are scarcely more than nubs!" Esarhaddon laughed. "Lad, come now; do not be so hostile. Would you rather fight me or sit upon my horse?"

"Fight you, sir!"

"Fight, lad? What foolishness is this?"

"No, foolishness, sir, but should you think to harm my mother, I shall surely fight you!"

"Instead of a tussle, we shall speak of things more pleasant. I have two sons; one who is a little older than you, and one who is a few years younger than you. Both of them appreciate good horseflesh, hunting and hawking... What is your name, lad?"

"Fródwine."

"I take it that the lady is your mother, and the other two are your brothers."

"Yes, sir," he replied. "She is my mother, and these are my brothers, Frumgár and Fritha." Fródwine tried to keep from gnawing his lower lip, a habit he had when he was tense. He wished he had a sword, and gave the slaver his fiercest look, frowning as he drew his lips into a tight line.

A small smile played across Esarhaddon's lips as he looked at Goldwyn. "And you, Madame, what is your name?"

"Goldwyn, sir." She knew she must not appear overly defiant, for that might bring even more of his unwelcomed attentions upon her family. The planned escape attempt, too, hinged upon her, for she was the instigator of the desperate conspiracy, and she must do nothing that would jeopardize the chances of the captives. Already Fródwine's boldness had aroused the slaver's interest.

Esarhaddon repeated her name several times. "You were given an appropriate name, for your hair is like spun gold reflecting in the sunlight. Doubtless a kiss from your fair red lips would taste as sweet as the richest of wine." The slaver turned to the nearby guard. "Release the woman! I wish for her to walk with me."

"No, sir, please!" Goldwyn felt dizzy with alarm, and in an attempt to calm herself, she concentrated on the horse's fine-tooled leather bridle and the thick red tassels which dangled down from the reins. "My sons are weary and hungry. Please allow us to go and eat."

As the guard unfastened the chain from Goldwyn's neck, she saw her eldest son looking at her, his eyes filled with confusion and anger. She sent the boy a warning look, but he only stared at her, his fists clenching.

"Dear lady, no one refuses me, so a protest serves no purpose." Esarhaddon smiled at her, his dark eyes gleaming with an interest that made her shudder. He was quickly off his horse, giving his reins over to a waiting groom.

Knowing his mother was upset, Fritha began wailing as Frumgár's eyes begged his young brother to be quiet. Fródwine clenched his fists so tightly that his knuckles turned white. He was close to hurling himself against the slaver when his mother clasped her hand upon his shoulder.

"Please, son, we will be all right."

Fródwine turned to his mother. "I do not like this," he spoke in Rohirric.

"No trouble, son! Please, no trouble!" she implored him in their language. "Just do what he says and perhaps he will go away and leave us alone. He has done nothing overtly threatening."

"Yet," Fródwine muttered darkly, holding his tongue. If only he were a few years older!

"Now, Madame," the slaver murmured smoothly as he took her by the elbow, "I would be pleased to show you and your sons about the dead city."

"Yes, my lord. My sons and I will walk with you," she told him in a voice that was edged with ice.

Fródwine glanced again at his mother, and he could see by the intractable look in her eyes that he would be a far wiser lad if he obeyed her. There was nothing to do now except stroll with the horrid man and pray that the interval would be brief and that they would soon be released to go back with the other captives.

Leading her around broken pieces of marble, the slaver steered Goldwyn towards a crumbling building. Trailing behind them, all three boys marveled at the destroyed splendor, and each tried to imagine what this stately wreckage once contained. Fródwine, though, scanned the ground for a shard or fragment of marble in case he would need a quick bludgeon.

Esarhaddon sensed unasked questions and answered them. "Since this decaying shell is on the perimeter of the city, perhaps it once held a guard tower, but there is so little remaining that it would be only a guess. I have been told that the library at Minas Tirith contains the early history of the builders of this city," he remarked jovially. "Boy," he looked over his shoulder at Fródwine, "can you read?"

"Yes, sir, some... in my own language."

"A good thing to know, boy." The slaver nodded his head. "Now what you need to do is learn all you can. Someday, if you are diligent and apply yourself to your studies, you might become a scribe."

'Yes, my lord," Fródwine replied sullenly. A scribe! Let this fat fool think what he wanted! He hated reading and writing. Warriors did not need to know how to read and write! All they had to learn was the skill of the sword, the axe, and how to fight with the eóred.

Satisfied with his answer, the slaver motioned them to follow him. "The widow is quite appealing," he thought to himself, wondering how her silky golden hair would feel when he ran it through his fingers.

"What is the purpose of parading through these buildings?" Goldwyn asked herself. "Does he seek to make light of my sons and me?" Nervously, she moved her fingers to her lips as she felt her already sweat-saturated armpits exuding even more moisture. She could barely withstand the reek of her own body. She thought with sudden amusement how at one time her state of filthiness would have caused her to be horribly embarrassed. The idea made her feel suddenly giddy. Now what did it matter if she smelled like a sow in a wallow?

"Madame?" the slaver was asking her. "Are you ill?"

"What a foolish thing for him to say!" she thought.

"Ill, sir?" Was she actually laughing? "Probably no more ill than any other slave who had been marched for days with little rest and less to eat might feel in the company of one of the men who holds her future in his hand." She waited for his reaction. Would he strike her? Would he hurt one of her sons? Would he flail them all with the riding crop which he used so expertly and take fiendish pleasure in driving the lot of them through the ruins?

Her mood of hilarity began to be overwhelming. Goldwyn wondered if perhaps now the strain of this unholy march had finally penetrated so deeply into her mind that it was shattering her wits and driving her mad.

"Then, Madame, I am glad that you are no worse off than any other," he replied dryly. "You are a saucy one." He sounded admiring as he clenched her elbow tightly.

"No better or worse than any other slave, sir." Saucy? she thought. How absurd! I am terrified of him!

"Mother," Fritha tugged at her skirt, "is the bad man going to kill us?" He spoke in Rohirric, for he knew little Common Speech, and his words were asked with a trembling lower lip and eyes close to tears.

"No, son," she replied comfortingly. "I do not think he is quite that evil."

"Madame, I do not understand your tongue, and unless your young son can speak none other, I require that you speak Westron so that I may understand."

"Pardon, sir. He speaks very little of any other language."

"Then he may be forgiven, but he should either learn not to repeat this error in the future, or keep silent."

"Sir, he is but five." She turned and looked into the slaver's dark eyes.

"The son of a beautiful mother," Esarhaddon's deep voice rolled like distant thunder in her ears. "How lovely she is!" he reflected. "How fair is her skin; the blue of her eyes, like gems of turquoise! Such delicious frowning lips, which beg to be kissed until they gasp in rapture!"

Goldwyn flushed, her eyes unable to meet his. "Sir, it is growing late. My sons should not miss their meal. Please allow us to go back."

"No, there is more that I wish to show you. Lads," Esarhaddon gestured towards the rubble, "explore this place while you have the chance, and have no concern for your mother. I give you my word of honor that she will come to no harm with me."

"If you break your word, sir, I will kill you!" His fists clenched, contempt and hatred on his face, Fródwine quickly stepped in front of the slaver and his mother.