Pelennor Fields, June 15, year 3019 of the Third Age under the Sun

As the sun rose that morning, worn shoes thudded upon the battle-scarred ground, weary feet traveling upon the same path that had once been battered by the thundering hooves of galloping horses. So at last, on the 15th of June, the very day of that ill-fated battle three months prior, the Rohirric captives came to the fields of Pelennor.

Though neither the captives nor their captors knew aught of it, another battle had been fought just the day before. Beyond all hope, the West had triumphed over the hordes of Mordor in fighting bloody and grim beneath the peaks of the Thrihyrne. It was the Second Battle of Helm's Deep, and after bitter retreat from the South, the Riders of Rohan and the men of Gondor had won glorious victory in the Deeping Coomb. To the dismay of the enemy and the answered prayers of the men of the West, a great force of Elvish warriors journeyed from the fair lands of the North and rode with the Riders of Rohan when they assailed the host of Mordor. Thus the battle was won, the day was saved, and the bruised head of the dark serpent drew back ere it could strike northward into Eriador.

Yet in Gondor, the plight of the captives was indeed a dismal one as they headed south towards the now conquered and occupied Minas Tirith. That morning, the orcs and Easterlings had broken their camp near the ruins of Forannest, the north-gate of the Rammas Echor, where they had spent the night before. Now the captives marched towards the sad White City which lay ten miles thither. No one would come to save them - not the Riders of Rohan, the Army of Gondor, or the host of the Elves - and there would be no escape from the evil days that lay before them. Their fate was now held in the hands of Mordor, a land ruled by a cruel and merciless Master.

The ground was damp in places from the rain which had fallen the day before, but most of the water had been absorbed by the thirsting earth. Still wide cracks rent the ground, like gaping mouths begging for another drink so that their thirst could finally be slaked. After three months of darkness, the sun at last shone freely, but the land before them was desolate and the restored light brought neither hope nor cheer.

The stench of death still lingered in the heavy air which had once been filled with the sweet scents of flowers and freshly mown hay. Once green earth was now pocked from the scars of thousands of hammering feet and hooves, and deep ruts caused by the wheels of heavily laden wains were riven into the barren ground. Rubble was everywhere, and the remains of brunt houses, broken siege towers and ruined wains were scattered all across the bleak landscape.

Far to the east, the dark peaks of the Mountains of Shadow, the impregnable walls of Mordor, were vague shadows of gloom upon the distant horizon. Burnt field and battered hill fell in sorrowful slopes towards the River Anduin. A land which had once been green and filled with plenty had been ravished and defiled. Gone were the town lands and homesteads, felled had been the orchards which once bloomed in the spring and bore fruit in the autumn. Even if some brave plant or thorn had dared to take root in the fire and battle-scorched ground, it would have quickly withered and died for want of light and water during the months of darkness. Many of the streams had gone dry in the drought, but now at last after the rain of the day before, a trickle of clean water flowed through parched channels once again.

Rising out of the plain before the column lay the bony wreckage of some enormous giant. Strips of weathered hide dangled down between the ruined framework of its body. Atop the massive rib cage perched a carrion-bird preening its feathers. The stench was still intolerable, though the bird seemed unmindful of the reek. Many of the captives almost gagged at the lingering smell of death all about them, and wished that their hands were not bound so that they could hold the fabric of their garments over their noses.

The bird squawked at the column and flew into the air. Joined by his comrades which had been feasting in the depths of the moldering carrion, they screeched their objections at being disturbed. Swirling in the sky above the fallen corpse, they returned to land upon the points of the rib bones, glaring at the column as it passed. Flies, guests that knew the feeding was drawing to a close, buzzed angrily as some of the birds flew downward, returning to argue over the remaining leftovers of the grand feast.

Captain Zgurpu looked grimly at the skeleton and spoke with a low, almost reverent tone in his hushed voice, "The crop of death was so vast that the harvesters could not gather it all." He ordered the band to increase the pace of their march.

"The lads who took the field had the pick of the meat but I daresay there was too much flesh even for them," laughed Sergeant Glokal. "Now the carrion-birds gather the last of the crop, but there'll be a fresh one for them to reap in the North. Plenty of meat for orc, bird and beast!"

Some holding the sleeves of their tunics over their noses, the cavalry troop and their sergeant rode a distance away in front of the orc companies. All were glad that this troublesome duty would soon be over, and both the troop of horsemen and the orcs could head back to Rohan. All would miss the company of fair captives, and though only words, devilish winks and shy glances had passed between them, impetuous promises never meant to be kept had been exchanged between the troopers and the captives.

"Glokal, keep your voice down. It wouldn't do for the Easterlings to hear such talk," worried the captain. "They burnt all of theirs that they could find."

"That they could find," the sergeant whispered, "but they didn't find them all." His grin was wide, showing the gaping spaces where some of his fangs had been knocked out and the snags where others had been broken. "I might say, sir, that they did not have nearly as much lard on them as the strawheads, but there's some as like stringy meat. Say eating such makes 'em stronger. But give me the fat meat any day, streaked with lots of blood!"

"Don't let them hear you say that! No point in irritating them. So far, they have not been too overbearing this time. You know what unholy tempers the Southrons and Easterlings have. They'd as soon cut your gizzard out as look at you! The cavalry will be riding with us on the return, and if you want to keep your head on your shoulders, you'll mind your manners around them! We'll be back in the North soon enough anyway and there's feasting on the flesh of man and horse ahead for us!" the captain exclaimed gleefully.

"No doubt, the lads up there have already won all the battles and there will be few spoils for us," lamented the sergeant.

"Sergeant, the Northern campaign will take longer than you might think before we triumph. There's going to be plenty more in store for us there. Who knows what delicacies we might find, both to please the palate and the flesh... maybe even some stout, lusty wenches to take back to the dens."

"Ay', but right now these carrion-birds are giving me the creeps. Glad it's not my bones they're picking!" The sergeant shuddered as he looked up at the large black raven which glared at him from its perch upon a whitened hip bone.

Here and there across the fields, the great hulking skeletons of more mûmakil rose in stark relief against the rolling ground. They lay like ships which had been beached upon a dismal shore, battered and driven by a storm so violent that the ships had floundered before the cruel winds. Some stark white frames stood almost erect, listing only slightly, making a sharp contrast to the others who lay adrift upon the ground on their sides. Their bony spines rose into the air, great tusks extended from mighty heads now bellowing a cry unheard. They seemed to march in silent review, moving to a destination which they neither knew nor understood, but still going forward, plodding in their brute strength, summoned at their Master's call and doing His bidding. The dead cavalry of the mûmakil fought now in silent repose, still moving out to face an enemy who, like them, had been turned to bone.

Silent sentinels now, their great forms marked the path upon which the orc captain led the column. Few were his words as he urged them on, lost in his own quiet reverie. His men's mood matched his own, and little was heard save the distant croaking and calling of the carrion-birds as they reveled in the last meals of their fallen prey.

Even the sound of plodding iron boots, flails falling on slow-moving legs, and clomping of horses' hooves seemed to fade into a strange, muffled silence. Though the sun shone brightly, the field seemed cold and gray, as though it were locked in an eternal winter. The mûmakil watched through empty eye sockets, caverns of black upon white hills.

All of worth had long since been pilfered from the bodies of the dead. Now only plowed rubbish remained of once great shields, valiant helms and armor, strong swords, proud spears, arrow tips that once flew - whether hitting their mark or missing none could say - and nothing was left of a great host save a few fragments, scattered here and there like lifeless petals of death flowers strewn by a careless hand.

On the column marched, their quiet cadence out of harmony with the cries of the death birds which grew ever more distant. Skeletal hands with no arms seemed to beckon them forward, groping as though searching for some reason, some meaning, as to why they had been ripped so callously from the arms that once had borne them. Skeletons of horses, some with their bones poised as though in some gristly gallop, rushed ever onward into a battle now lost, their riders' cries of war hushed in death.

On they marched through the grim fields of decay, the reapers of the havoc now mixed with the crop. Both bone and skull of man and orc lay atop one another, and stripped of the flesh, scarce little difference could be noted between the two - bone upon bone, thigh upon thigh, shank upon shank, arm bone, knee joint, ribs and collar bones, foot and ankle, hand, arm and finger - all tramped by death into the same vintage.

The column seemed to slow its pace, held suspended, the dead and the living in lock-step together, listening to some herald, a silent tune played on drum, horn and pipe whose sound had long been stilled. One foot down, one foot forward, then another, and on to the next. Living and dead both marched to a slow dance of death.

Before them now lay a broad avenue, marked at its borders by a line of poles, each mounted with its own skull who smiled a grim greeting to the column - captor and captive alike. The lifeless heads grinned down upon them in a sure knowledge that soon the one would be like the other. The sepulchral mouths pronounced a silent benediction - "As I am now, so shall ye be."

Some of the skulls had inscribed upon their foreheads rude etchings, while others had dull red paint to mark the eye sockets. Here and there a proud Rohirric helm, crushed and battered, crowned the brow of a skull. Under each grinning head the poles were festooned by streamers of braided horse manes and tails adorned with dangling lines of knuckle bones held together by hair the color of straw.

Elfhild stared in horror at the skulls, some morbid fascination holding her mind in its clutch, and she gawked at the ghastly markers, unable to look away. Once those empty eye sockets had been covered with flesh and held blue eyes which had flashed in anger or twinkled merrily or shed tears of mourning. Did they sorrow even now for the living? Did their shades wander in loneliness through the night, singing songs of lamentation, the spectral keening of the brokenhearted ones who lingered behind?

She wondered how each one had died. Had their heads been cruelly severed in the heat of the battle, or had they fallen by other means: the spear through the heart, the gash of the sword, the piercing blow of the arrow? Had they languished in agony, pierced by mortal blows? Had they suffered, or had the end come mercifully quick? How does one count the measure of suffering? Did the enemy laugh at the moans and shrieks of the wounded as they futilely tried to crawl away? Had the orcs pilfered the forms of the fallen, eaten the cooling flesh of the dead - or even worse, the still throbbing muscles and sinews of the wounded - and then finally turned their wicked hands to making vile markers out of the heads of brave Riders? Elfhild shuddered at these macabre thoughts.

The captives solemnly shuffled by the two rows of columns as though in a belated funeral march, almost hesitant to leave the gristly sights of death behind them. Could living hands offer comfort to the slain? Could they hear the wails of the mourning? Could still hearts feel the throbbing of those who were still alive?

The lifeless gaze of one skull in particular seemed to grasp at Elfhild's heart, causing her breath to catch in her throat. A silent exchange passed between living and dead, and she reeled from the sudden knowledge. In that moment, she knew that she now beheld her father, as though his skull itself had spoken to her. Perhaps it had...

"No..." she whispered, but the sagacity held within the shadowy pools of that head now barren of flesh could not be denied. The bitter truth unfolded itself before her as a scroll inscribed with bold black letters written by the heavy hand of merciless doom, and her heart read clearly what was written there.

"Father," she whimpered. "Father? Eadfrid?"

There was a certainty that they knew that she was here. She longed to reach out for them, to join them and to comfort them in the lonely silence of the slain.

"Keep marching!" an orc snarled.

"Can you not let us mourn!" Goldwyn's beautiful voice rang out harsh and savage, like a discordant note in an otherwise lovely song.

"Damn whores, keep moving!" the orc cursed as he brought the flail down across the backs of her legs. Their heads turning to look backward, the widows and orphans stumbled on as they began to chant a low keen of mourning.

"They are dead... all dead," Elfhild whispered to her sister beside her. She closed her eyes tightly, forcing tears to spring forth from crystal pools held by her lashes.

Elffled nodded gravely. No further explanation was needed. She knew exactly of whom her sister spoke: their father Eadbald and brother Eadfrid. Yet she wept not, for how can ice caught in the darkest depths of winter melt into cascading waterfalls? Cold she was, numb and nerveless, the icy chill of incomprehensible sorrow curling itself about her heart like a billowing wind of snow and frost.

"Our hearts are broken and so they will remain until death take my sister and myself, and mayhap then we shall find peace. Orphaned, homeless, slaves," Elffled thought despairingly, "the tale of our years shall end in sorrow and woe, and evil will be all our days." She cast a furtive glance back at the skulls. "Perhaps they are the fortunate ones, for they are beyond pain. Perhaps they mourn for us, for we are yet alive. Though they lay not in hallowed mounds and the enemy flaunts their earthly memories as tokens of defeat, at least thralldom and bondage shall never be their fate." Darkness clouded Elffled's mind and she stumbled forward with the rest, blind beggars lost in a storm of unending gloom.

A triumphant march, a processional parade welcomed by the smiling faces of death, footsteps falling silently, heralded by the lines of poles - the column marched on.

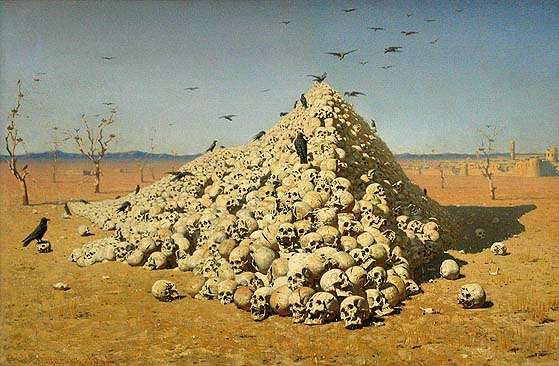

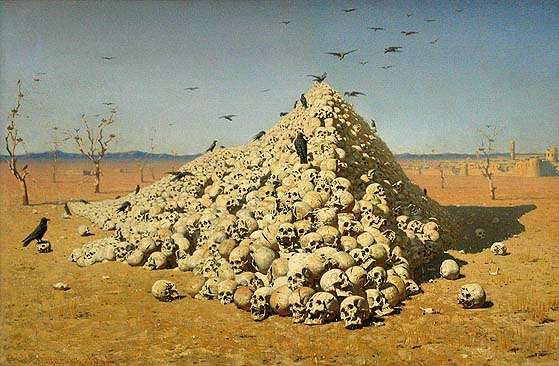

At last they came to the end of the procession route. The path led on around a small bend and there awaited a stark, a pale mound flanked by two smaller knolls. Vast quantities of bones of horse and man all lay piled together, white mounds of strange simbelmynë.

The cavalry troop had halted at the base of the large mound and the orc captain gave the order to his men and the captives to stop. The captives, too numb by the stark terror of the sights which they had beheld, had shuddered when the realization had befallen them that this must be all now that remained of those fathers, husbands, sons, brothers and kin to whom they had so proudly bade farewell but a few short months before. Many wept openly while others muttered disbelieving whispers. The children cried and the little ones clung to their mothers' skirts.

Sergeant Utana turned aside from the mound as his troopers went on. He rode his horse down the line of prisoners and spoke to them soft words in Westron. Those who could not hear his words wondered what he had said and thought dark thoughts that he was gloating and boasting of the great havoc that his people had helped to bring.

When he drew near the space of Elfhild and Elffled's troop, he halted his horse again and looked above their heads. As he spoke, his face took on the features of a prophet who had been divinely blessed, and his words rained down upon the captives like judgment.

"Your group is the first among many Rohirric slaves yet to come to behold the sight of this field. Perhaps you had wondered why during the twenty-two days of your captivity that no one had revealed what had happened at Pelennor. It was decided some time ago that the answer to all your questions about the battle and the fates of your families would be given here as a warning to you of the high price of resistance against a righteous force. You know without my saying who were the owners of these bones. Thus it will always be when usurpers and their allies attempt to resist the realm of the rightful King of Men and Lord of Middle-earth!

"Your men made a most grievous mistake when they set the course to help their allies and to wage a war they could not hope to win. At least now, wherever their spirits might have fled, they are probably free and enlightened as to the follies of their ways. While I am most proud of the great victory achieved here three months ago today upon the 15th of March, I do offer my condolences to you, their widows, sisters, daughters, and kin. There is little I can say to you other than this: you may rest with the knowledge in your hearts that your children will be born in a land that has been brought into the light, and know that the only true way to peace comes through the wisdom and power of the Great Master whom you have called, up to now, 'The Enemy.' Now you will learn the way of discipline and call Him by the title He so rightfully deserves: 'Master!' May the fruits of your wombs be bountiful, blessed by the seed of your superiors!"

From the midst of the low dirge that the women were chanting, Goldwyn's clear voice rang out. "You are all the filth of dogs!"

"Gag her and any more who dare interrupt me!" Sergeant Utana shouted, furious that any had dared challenge his words.

When the woman had been silenced, the sergeant looked up and down the line of captives to see what other reactions which his words had brought. Reading only sadness, disbelief, and anger upon their faces, he resumed speaking. "Though you do not realize it now, a great honor has been paid to all of you. You could just as well have been slain where you were, or turned over to the troops for their sport, but our Master desires rule and order. Therefore for the benefit and protection of His subjects, in His omniscient knowledge, He has laid down wise laws for the governing of all; therefore, according to His designs and wisdom, you have all been spared that.

"Though some of you can look forward to a future as mothers of a new, stronger race of uruk-hai, others shall be the concubines of your conquerors. I am pleased to tell you, though, that a few of you have a far more glorious fate in store. Those who are chosen will be ushered into a state of blissfulness and radiance to which few mortals could ever hope to aspire. You will be the consorts of the Dark Gods!" He smiled benignly upon them. "In all things, learn to rely upon the benevolent graciousness of your Great Master!" The sergeant's eyes gleamed in a kapurdri-induced trance.

"I doubt that further words will ever pass between us, for after you are taken to the City, we must go north to help finish the fight that was begun here. Farewell," Sergeant Utana bade them as he turned his horse and rode past the orc companies back to the head of the column. Then he and his troopers trotted out of their lives and rode towards Minas Tirith.

"March!" Captain Zgurpu gave the grating order. The company moved forward, their eyes straight ahead as they skirted the great heap and passed between the larger and the smaller of the piles. Women softly moaned and children whimpered, their hearts stricken by the blackest of grief. Pale rising clumps of spectral white and gray, unhearing, unseeing witnesses of the life that went by them, the withered mounds did not mark the coming and going of any.

The ground steadily rose before the column in an a gentle incline and the bones and fragments of war became fewer and fewer. At last before the prisoners lay a broad expanse of cleared ground. The whole mass of orcs and prisoners breathed a great sigh of relief. The captain's shoulders relaxed almost unperceptively, although his sergeant was quick to catch the movement.

"Garn!" Captain Zgurpu exclaimed, almost merry. "That was a royal feast for the lads after the battle, and now there ain't nothing more than a dry bone upon which to gnaw." In truth, he had been filled with fear at the sight of the bones of so many of his kind. An officer never showed weakness before his men, though, for they could turn on him in an instant and rip him into pieces.

Now freed of an unseen yoke, the marching feet increased their tempo. "Won't be long now," the captain called over his shoulder, "'til we're free of the wenches and their squalling brats! And, lads, it'll be a bit of rest for us! You can be sure that the draught'll be flowing freely to celebrate these prizes that we've brought! In the City, we'll turn our charges over to others, and after a night's rest, we'll be on our way back to battle and they'll be on their way to their masters' beds."

He laughed and the lads behind him cheered, some raising their spears in gusto at his words.

The spell of silence now broken, the captives slowly began to feel once again, to let coursing thoughts of white, grim starkness coil themselves about their minds. They were just beginning to fathom a small measure what they had just seen. Some were in denial and would not think about what they had beheld, pushing the thoughts back to dark corners of their minds. Others let the full, harsh horror envelop their souls in a crushing vice of despair. Every bone, every skull, every broken shard... was it the husband, the father, the brother, the uncle well beloved, the friend or lover?

The wails of sorrow clutched at the captives' throats and they were unable to give vent to their anguished screams. Only a few children sobbed, more from dread than from realization. Silence again fell and then a great moaning. It was too much to bear. Then like dark, rushing waters, piercing shrieks rent the air, crying out to whatever Powers would give heed and solace.

Death lay behind the captives. What lay before them? The dead had no answers.

So it is when glory, honor, and valor die... the silent cry stilled in the throat. So brave the warrior, so white the simbelmynë, the flower of death, upon the fields of the slain.