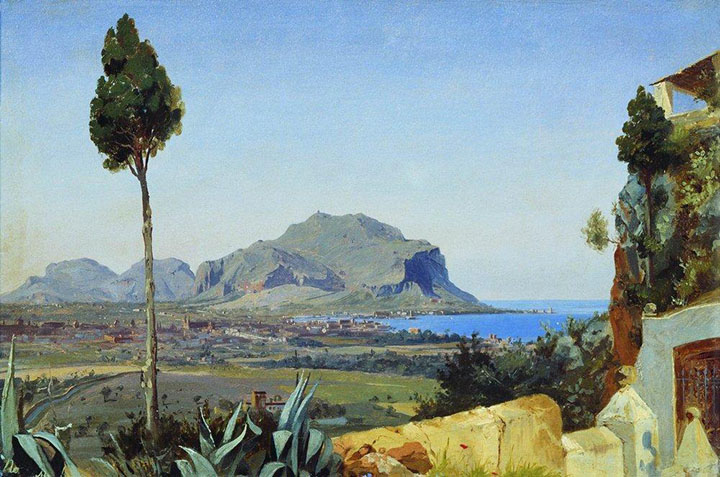

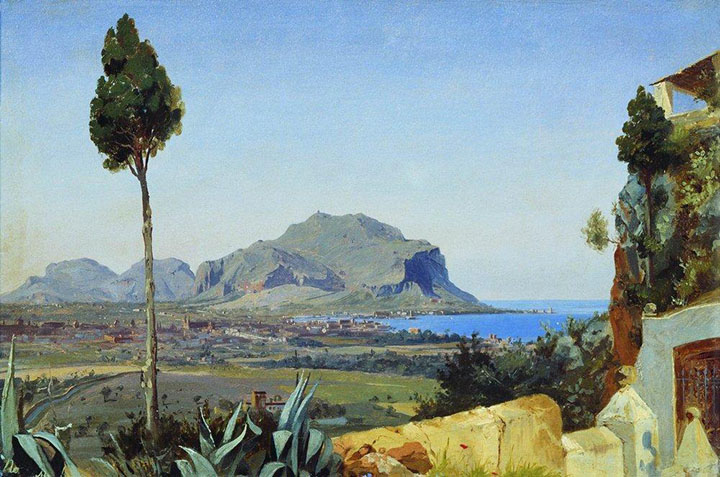

The last remaining days of the journey passed with little of importance happening, but the sights which the captives saw filled them with delight. To travelers who had spent many months journeying through the desert, the beauty of Nurn always came as a shock, the mind reeling at the sudden change of scenery. Grass actually grew here; a beautiful green carpet which spread out over the plain, not the scrubby little tufts which dotted the desert sands. Sheep, goats, cattle and horses grazed upon rich pasture fields, watching curiously as the captives walked by. Orchards were everywhere, the boughs of the trees heavily laden with apples and pears. The wheat fields were freshly harvested, the stubby stocks of the cut grain shining golden in the sunlight. The air was filled with the singing of birds, with the occasional song of laborers in the fields blending into the melody of nature. Everything was so bright and green here, and the captives gawked in amazement at their surroundings. It was like waking from a nightmare to find that the Sun still shone and flowers still bloomed.

The roadway followed the course of the River Mormilom, and as the captives traveled southward, they gazed in wonder at all they beheld. Years before, a vast system of canals leading from the river had been constructed to divert water to the parched lands on either side. Located on the eastern side of the river, the largest of these canals was ninety feet across, nearly ten feet deep, and extended for a distance of thirty miles. The ditches decreased in size the farther away they were from the river, making for a more even flow of water. When necessary, the control gates were closed, causing the current to back up and making it possible for the farmers to regulate the flow down channel. Orchards, vineyards, crops, flocks, pastures and gardens flourished in the rich volcanic soil, fed by the life-giving waters of irrigation ditches drawn from wells or the river.

Strict rules regulated the use of the canals and feeder ditches, with dire penalties for anyone who used more than their allowance of water or hindered the flow. As long as the water system was unimpeded, the crops grew, trade prospered, the nobles and merchants were happy, and even more importantly, the Great Master in His Dark Tower was pleased. When He was content, the wealthy were allowed to live their own lives with few restrictions, but when He was not, the offenders would be removed in a bloody purge.

Over the din of the caravan, the captives heard a persistent creaking sound echoing harshly over the plain. As they passed by the source of the noise, the captives warily eyed the strange apparatus, its like unknown in Rohan. Groaning and creaking, two great wheels, one seated over the top of the other, slowly turned on the bank of the river. Each wheel held buckets suspended on chains. As an empty bucket dipped down into the river, it came back up filled to the brim, emptying its load into the higher channel. The sound of the water splashing into the ditch would have been almost peaceful were not for the muted groans of the sweating slaves who turned the levers which operated the apparatus.

Mud-brick villages and sprawling villas dotted the countryside through which the captives traveled. The women and children had never seen such grand structures, and the homes of mere merchants seemed like palaces to them. There were other travelers upon the road which held their interest as well: small caravans bearing food and supplies for outposts located in the wastes of Gorgoroth; villagers on the way to local markets; herdsmen driving their flocks and herds; couriers bearing missives and parcels to distant villages and cities; and chained parties of slaves headed for the fields or the mines in the north. Wealthy travelers rode in palanquins borne by slaves or in elaborately decorated wains pulled by the finest horses. Every now and then, a small party of dark robed men and women would travel past the caravan, often singing and chanting in Black Speech. The guards explained that these were pilgrims on their way to Barad-dûr or Minas Morgul, or even the woodland fortress of Dol Guldur or the old kingdom of Angmar far away to the north.

As the caravan journeyed southward, a great body of water began to materialize upon the horizon, stretching as far as the eye could see. Coming from a landlocked country with few large lakes, the captives had never seen so much water before, and some mistakenly thought that they beheld the Belegaer. The guards were amused at their innocence, and informed the captives that they were nowhere near the great ocean; this was the Sea of Núrnen, one of the largest inland seas in all of Middle-earth. As the captives drew closer to the sea, some saw something which they had never seen before: boats. Along the coast, the surface of the water was dotted with merchant ships, ferries, and fishing crafts which sailed to and from small fishing towns near the shore.

Though the Sea of Núrnen had no outlet, four major rivers and other smaller streams flowed into it. Near the mouths of the rivers, the water was fresh to brackish, unlike the northern and central parts of the sea, which were saline. Though freshwater fish soon died after they were swept into the salty interior, a unique type of fish had developed over the course of many years. Equally at home in both fresh and brackish waters, the red poshak was known to reach lengths of a foot or even longer with weights of several pounds, making them a valuable catch for local fishermen. These fish were said to have a mild flavor, and were excellent when wrapped in grape leaves and grilled, then drenched with lemon juice and olive oil. It seemed that every tavern along the coast had its own special recipe for the poshak, vaunting their culinary talents as among the best in all Middle-earth. Besides providing a tasty addition to the local fare, the fish of the Sea of Núrnen were a valuable source of income, generating jobs and revenue for many. Dried and smoked fish were produced in many towns along the coast, and transported to locations all over Mordor, contributing goodly sums to the coffers of merchants.

As the caravan approached the confluence of the Mormilom River and the Sea of Núrnen, they saw the great fortress of Durbûrzkala perched high atop a cliff overlooking the sea. Situated on a sandstone bluff two hundred feet above the surrounding countryside, the fortress was the dominant feature of the landscape and could be seen from miles away. A road led off towards the fortress and crossed over a bridge spanning the river, winding its way up the steep hillside. Three walls encircled the fortress, each wall rising above the other. Constructed in an architectural style little known in the West, the walls were built of massive semicircular towers, each joined to the other. Many of these towers were constructed with open inner walls to facilitate the movement of men and supplies from one point to another.

Between the first wall and second lay a steep slope which would present a great obstacle to any enemy force which had managed to storm the gates. Should an invader pass over the first and second walls, he would be faced with the grim bastions of the third wall which towered above the lower levels. Narrow slits scored the walls where archers could send down a rain of arrows upon an approaching enemy. Any who gained one of the areas between the walls would face a killing field at each level. The third wall enclosed the heart of the fortress – a broad practice field for the garrison; a stable; kitchens; a temple dedicated to the worship of the Dark God; government buildings; and the residence of the commanding officer.

Rising above the third level, crowning the height with its grim presence, was the Tower of Durbûrzkala, the last obstacle an invading force would have to overcome in its conquest of the fortress. No enemy had ever breached the walls of the fortress, and through the years, the high keep had other purposes, dark and grim. It was said that the screams of those tortured there over the years could still be heard echoing down its blood-drenched halls. Besides the walls and gates, other baffles and foils had been created to thwart an enemy. As the main road through the fortress curved up the hill, it twisted sharply in a number of places, zigzagging back upon itself. With its broad slaughter fields, its massive iron, bound gates and treacherous maze of roads, Durbûrzkala was an almost invincible challenge to any enemy.

After passing the bridge which led to Dubûrzkala Hill, the caravan journeyed for another day, and then at last, upon the eighteenth day of August, the captives caught sight of the domes and spires of a great city in the distance.

This was Turkûrzgoi, greatest of all Nurnian cities and the jewel of Southern Mordor.

Much of the history of Turkûrzgoi has been lost to the West, but the scribes of Mordor write that the city had been almost continuously inhabited by Men since ancient times. Located near the Sea of Núrnen, the city was built along the Tornîn River which flowed down from the Mountains of Shadow in the west. Over the years, the walls of the city had spread to both sides of the river, with the larger part of the city being on the north side, and the smaller, newer city on the south. In addition to a fortified bridge, several ferries connected the two parts of the city.

Turkûrzgoi was accessible by land and water, and in addition to its advantageous position, the city owed much of its prosperity to the rich agricultural lands which surrounded it. Situated upon a crossroads, the vast city had many gates from which roads led north, west and south. Caravans were always arriving and disembarking from the city on their way to northern Mordor. Besides its other advantages, Turkûrzgoi was home to many merchants, trading houses, granaries, warehouses, factories, tanneries, markets, and inns. The Tornîn River ran through the southern half of the city, and a healthy riverine trade had grown up around the river. Docks and warehouses lined both banks, and gristmills flourished, processing the great quantities of grain which the province produced.

Besides being the center of commerce for western Nurn, Turkûrzgoi was also its primary center of religion, with dozens of temples dedicated to the Dark Religion. There were elaborate temples for devotees of Melkor and Sauron, and smaller shrines to servants of the Dark Lord, such as the Nazgûl, who were worshipped as lesser deities by many people. Turkûrzgoi boasted cultists of every variety, from violent zealots who wished to wipe unbelievers from the face of the earth to moderate devotees who were more accepting of infidels.

Turkûrzgoi was also a center of learning and culture, boasting a university, observatory, library, and hospital. The Library of Turkûrzgoi, with its expansive collection of ancient scrolls and tomes, was famed throughout the province. Many local scholars claimed that only the vast libraries of Barad-dûr could ever rival the information contained within the Library of Turkûrzgoi. Scholars from all over Nurn came to the University of Turkûrzgoi to study such subjects as history, natural philosophy, alchemy, and mathematics. The University's observatory provided a high tower where learned astronomers and astrologers could study the stars, but the backward and ignorant were convinced that its true purpose was to summon the Ancient One from the Void. Such a concept presented a dilemma, for many were unsure where their allegiance would lie should Melkor return, whether it would be with Him or the Master of the Dark Tower. The ancient prophesy stated that when Melkor returned, the final battle of the Gods would be waged, and the world would be destroyed. After finally defeating the Valar, Melkor would create a new world and reward His followers with wealth, power, and eternal life. However, a great many of the people of Turkûrzgoi liked their old world just fine, even though it had an abundance of faults. As puzzled and confused as these people were, those who were familiar with the teachings of the West were even more conflicted, for the Gondorians maintained that in the final battle, the Valar would be triumphant and Melkor would be the one who was vanquished. Such unanswerable questions sometimes drove men mad.

Though the observatory posed both intellectual and moral dilemmas, the hospital was a certainty in an uncertain world. The facility treated both minor and serious injuries, as well as chronic conditions and rare diseases. In addition to treating various maladies, the hospital also provided a small school for training healers. Although the city contributed to its operations, most of the funds necessary for its maintenance came from contributions. At the hospital's inception, its founders had insisted that no patient should be turned away, no matter if he had not a copper to his name.

Tushratta was one of the men who had helped found the hospital, using much of his own finances to help fund the project in its early stages. When he was not journeying with Esarhaddon, he was working at the hospital, either administering to the sick and afflicted, or teaching in the small medical school. He took no pay for his work among the poor, charging only those who could afford his services. The healer, of course, was eager to return to the city, for he was in a great haste to be back in his hospital. He fretted that something might have gone wrong in his absence, and he tried to relax his mind by reciting silently to himself the number and names of the bones in the body. No one would know his agitated state of mind, however, for his expression revealed nothing, only his usual calm demeanor.

As they looked at the great city in the distance, the captives' thoughts were on their uncertain future. Some had given up hope, resigning themselves to be helpless victims, tossed and turned about as the chances of life dictated. Others, whose natures were more resilient, dared to hope that their new lives might be better than the ones they had known in the Mark. There was nothing for them to return to in Rohan anyway, for they had been told that everything in that beleaguered land had been destroyed, pillaged and looted, and was now occupied by the enemy. A lie, of course, but they had been told the tale so many times that many were willing to believe it. Some of the guards and servants of Esarhaddon seemed sympathetic to the plight of the captives, and tried to build up their spirits by assuring them that they would be sold to wealthy households, where all their needs would be well provided for. Some women, though, like Goldwyn, considered that all enemies were liars, and believed nothing, whether good or bad, that they were told.

Another hour of marching, and the captives saw the walls of Turkûrzgoi rising before them, its sandstone blocks dull red in the light of the late afternoon sun. A great blare of trumpets rang from the top of the parapets in greeting, and were answered by the caravan's own trumpeters, who, while sounding a bit off-key, at least had enthusiasm. Banners hung from the gatehouse wall, and flags high atop the parapet snapped in the breeze. If the appearance of the city counted for anything, the caravan's arrival at Turkûrzgoi was an auspicious one. The guards cheered and waved, their faces lit up in smiles. Eager to be home, the guards hurried the captives along, although their flails slapped only the legs of their slowest charges. Impatient to go to his place of business and greet his brother after so many months, Esarhaddon rode ahead to the gatehouse, where his papers were quickly approved, and the officer there sent him into the city.

The long line of captives, marching two abreast, moved slowly towards Turkûrzgoi. As they drew nigh to the city walls, the whole long serpentine line seemed to shudder, drawing back in apprehension. Although the trumpets still rang out exuberantly and the city's flags snapped smartly in the wind, it seemed all had changed, and a gray cloud of gloom blighted the captives' minds. There before them, beneath the city walls, was a gristly sight which would make even the blood of the brave grow cold.

Twenty or so men and women had been impaled upon tall posts driven into the ground before the walls. Most were dead, but a few moaned and thrashed about as they waited for death to relieve them of their agony. One man, his eyes fixed upon the approaching caravan, let out a loud shriek and twisted in the throes of pain, his frenzied movements driving the stake deeper into his body. Hanging from a section of the wall near the gatehouse were severed heads, their sightless eye sockets silently viewing the grim execution. A chill passed through the captives, and many could not bear to look at the sight. Some, gripped by the macabre terror of the scene, became violently ill and vomited along the side of the road. The caravan was forced to halt so that the guards could remove the sick captives to the medical wains.

"Master, what is the meaning of all this?" Elfhild timidly asked the guard who was riding nearest to her. "Why have all these people been condemned to death?"

"Hmm, there are more than usual." The guard scratched his bearded chin thoughtfully. "Perhaps there was a slave uprising while we were gone. Only those who have committed the most abhorrent of crimes are executed in such fashion, their bodies exhibited before the city gates as a warning to those who would dare break the laws of Mordor."

"Are there many slave uprisings, Master?" Elfhild was frightened even to ask, for the very question might be forbidden. Yet the knowledge that there were those in the very heart of the Dark Lord's realm who were willing to defy Him caused her to feel a hope she had not felt in a very long time.

A suspicious look upon his face, the guard gave Elfhild a long, hard stare, causing her to avert her gaze in intimidation. "Most slaves in Nurn are content with their lot in life, for it is a great honor to serve the Giver of Gifts. However, from time to time, some deranged zealot gets it into his or her brain that it would be a good idea to rebel against the Lawful Ruler of Middle-earth." He gestured around at the gruesome display of the dead and dying. "As you can see, this is the fate that awaits all those who dare to oppose the might of the Great Eye."

What a cruel place in which they had found themselves, Elfhild thought to herself. But it was Mordor, was it not? What could they expect in the land ruled by the Dark Lord?

Dazed and repulsed at their first close glimpse of the city, the captives tried to steel their will for what might come next. After they had passed through the city gates, it was as though they had been ushered into another world where carefully tended shade trees lined either side of a broad paved area. Bright, colorful birds twittered and chirped in stately plane trees, some birds angrily scolding a sleek cat who dared to watch them from a limb. A guardhouse stood to one side, providing lodging for the men who watched the gate. Many of the structures which faced the square were modest in appearance, but there were several wealthy homes which boasted intricately stuccoed facades, colonnaded walkways, and elaborate arched doorways. At the center of the square were several palm trees whose fronds swayed softly in the breeze; a small garden of late summer flowers had been planted beneath them and added color to the sandy pavement. A splashing fountain provided water for thirsty travelers and their animals. Litter bearers and porters loitered about along the sides of the square, hoping to make a few coins by transporting people and goods throughout the great city. A crowd of onlookers had gathered to gawk at the caravan and its cargo of exotic, foreign slaves, but the city guards kept them from drawing too close.

Moving several hundred people – as well as wagons and animals – took some time, and so the captives faced a long wait as the courtyard slowly began to fill. The great mass moved slowly through the gate, grinding to a halt from time to time and then moving forward again as the captives in the forefront were herded into the courtyard. Horses whinnied impatiently, tossing their heads and pawing the ground, skittish at the new sights and smells of the great city. Small children held to their mothers' skirts, uncertain what to expect in their new surroundings.

After the last wagon had passed through the gate, the caravan made its way down a broad avenue: the Mûl Khamûl, or the Way of Khamûl, named for the immortal sorcerer king who united all of Nurn in ancient days. The great street ran north to south down the center of the city of Turkûrzgoi, and many side roads split away from it like the branches of an enormous tree. At the heart of the city was Bûrzgûl Square, an enormous, grassy area with a long, rectangular pool at its center. Dozens of water jets sprayed playfully across the shallow pool, splashing and tinkling merrily. Roses had been planted around the edges of the water, and the pool was surrounded by a border of scarlet. Other fountains and pools dotted the square, but none were as large as the central one. The greenness of the field was divided into verdant sections by paved walkways, with symmetrically planted trees forming neat rows across the square. When compared with the yellow, white, and orange buildings which surrounded it, the square shone as an emerald in a golden setting.

The captives felt a sense of fleeting peace in this beautiful, magical place, their minds eager to forget the gruesome horrors which they had seen before the city gates. The crowd which had gathered to watch them as they came into the city had gotten progressively larger, and curious onlookers flanked the procession of the caravan. Already a lively place filled with noise and activity, the city square exploded into a cacophony of hundreds of voices talking, shouting, and singing all at once, the sounds melding together into one continuous hum. Water bearers gave out free cups of water, courtesy of local vendors and merchants. Enterprising street entertainers gathered in the square, hoping to catch the interest of the crowd. The captives watched the spectacle in amazement. There were musicians, dancers, jugglers, puppet masters, and performers with trained animals. Beggars tried to win the sympathies of the crowd before the guards had a chance to drive them back to their alleys.

The captives would have been content to have spent the rest of the day in Bûrzgûl Square, but the guards hurried them along, more than glad that their part in the journey was almost finished. Turning east, the caravan traveled down Market Street, which housed the Great Bazaar of Turkûrzgoi. The captives passed by endless stalls, shops, tents, taverns, and tea houses. Branching off from the main thoroughfare were roads with such names as the Street of the Tin Makers, the Street of the Basket Weavers, the Street of the Booksellers, and the Street of the Perfumers. The smells of the city were heavy on the air: exotic spices and fish, incense mixed with animal dung and garbage. Merchants cried out in loud voices, advertising their wares.

Such wondrous sights and aromas distracted the captives, and they looked with wonder at all the marvelous sights. Here was a seller of beautiful silver jewelry, and there was a cloth merchant who was smiling as he showed off a bolt of chartreuse silk which had come all the way from the Far East of Middle-earth. Sitting under the protection of colorful striped canopies in front of tea shops, diners stared at the procession of captives as they passed by. Rare and exotic caged birds added their calls and warbles to the general din of the city, but the captives' eyes opened wide in amazement when they saw a strange furry brown creature chattering and doing tricks at the command of a street entertainer. Such was the Great Bazaar of Turkûrzgoi, or at least a small part of it. Never before had any of the women seen anything like the glorious bustle and confusion of the marketplace, not even at fairs back in Rohan.

At the end of Market Street stood a large and imposing sandstone building stuccoed in a shade of white. Rounding the front of the structure, the long line of the caravan began to creep through an alley. Up ahead was a gate guarded by two fierce looking men who held wicked-looking spears. The men drew open the gate, and the caravan guards directed their charges into the center of the courtyard that lay beyond. When all of the captives had arrived, the gates were closed behind them, but the guards remained. With the possibility of escape no longer viable, servants came forth to release the women and children from their bonds. They were not allowed to break rank, however, and each troop of ten was instructed to remain standing in orderly rows while scribes recorded their names and numbers. This process took quite a while, and as the women and children were waiting, they were given water by servants.

After a few moments, the captives heard a voice from a balcony above, and looked up to see the speaker, a stocky man dressed in fine robes. Beside him stood Esarhaddon, along with a man so similar to the slaver in appearance that surely the two must be brothers, and another man dressed in the black and red livery of Mordor. "Welcome to the House of the Golden Chain, the culmination of your long journey," the speaker proclaimed in a magnanimous voice. "I am Tuzug, chief of the auctioneers of this fine establishment. How marvelous it is that so many of you have reached here safely! I know that you must miss Rohan, but Mordor is now your home, and you will grow to love it as much as you did your old land." He paused, letting them become accustomed to the concept, but when he saw the expressions of doubt on their faces, he smiled benignly.

"You perceive Mordor as the wicked invader of your country, but you believe that only because you are the victims of the lies that your people have been told for hundreds of years. Your neighbors, the Gondorians, are far from the noble, heroic people that they would wish you to believe. For centuries, they have lusted for the lands of Mordor, wishing to claim the mineral riches of the earth and the fertile, volcanic soil of Nurn. Even though the Gondorians were bent upon a war of expansion, they did not have the strength to invade Mordor on their own. For this reason, they sought to enlist the aid of Rohan, their ally for many years, in this foolish endeavor, and to affect this folly, they filled the mind of King Théoden with lies. They made him believe that Gondor was the victim, rather than the perpetrator of this unjust war! King Théoden trusted them, believing the falsehoods of Gondor!"

Some of the captives were angered by the claims of the Chief Auctioneer and refused to believe a single one of the man's fair-sounding words, while others began to question all that they thought they had ever known. Holding up a hand to silence the murmuring of the crowd, Tuzug continued his speech.

"It is a terrible thing that you, innocent civilians, had to suffer because of this bloody conflict. I beg you not to hold any resentment in your hearts towards Mordor. You must realize how loath the Great One was to wage war upon the West, but the treacherous machinations of Gondor gave him no choice. The Great One is often called Annatar, the Giver of Gifts, and in His wondrous mercy, He has taken pity upon you by bringing you to the heart of His realm and allowing you to labor for Him. In time you will fall upon your knees and offer praises to Lord Annatar for His beneficence. Put aside your old lives as Rohirrim and embrace your destiny as Núrniags, for all of you are of Mordor now! I bid you welcome to the land of endless blessings!"